Research suggests that the representation of violence against women in the media has resulted in an increased acceptance of attitudes favoring domestic violence. While prior work has investigated the relationship between violent media exposure and violent crime, there has been little effort to empirically examine the relationship between specific forms of violent media exposure and the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Using data collected from a sample of 148 inmates, the current study seeks to help fill these gaps in the literature by examining the relationship between exposure to various forms of pleasurable violent media and the perpetration of intimate partner violence (i.e., conviction and self-reported). At the bivariate level, results indicate a significant positive relationship between exposure to pleasurable television violence and self-reported intimate partner abuse. However, this relationship is reduced to insignificant levels in multivariable modeling. Endorsement of domestic violence beliefs and victimization experience were found to be the strongest predictors of intimate partner violence perpetration. Potential policy implications based on findings are discussed within.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In the United States, more than 12 million men and women become victims of domestic violence each year [76]. In fact, every minute, roughly 20 Americans are victimized at the hands of an intimate partner [3]. Although both men and women are abused by an intimate partner, women have a higher likelihood of such abuse, with those ages 18–34 years being at the highest risk of victimization. Moreover, it is estimated that approximately 1 in 4 women and 1 in 7 men experience violence at the hands of an intimate partner at some point in their lifetime [77].

According to the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women [78], the representation of violence against women in the media has greatly increased over the years. Recent research suggests that women are commonly depicted as victims and sex objects in the media [12, 69]. Portraying women in this way, media via pornography, pornographic movies, and music videos, has been found to increase attitudes which are supportive of violence, specifically sexual violence, against women. Notably, in relation to violence in general, research suggests that the media’s portrayal of women as sex objects and victims, tends to influence societal attitudes that are accepting of domestic violence, particularly violence against women [40, 43, 46, 69].

Understanding the influence of media violence on an individual’s perceptions of domestic violence could help gain a better understanding of the factors that contribute to an individual’s domestic violence tendencies, as well as to gain a better understanding of how to lessen such tendencies. Not only can the influence of media violence on domestic violence perceptions be addressed, but specific media forms can be identified as to the level of influence that each form of media has on such perceptions as well. Understanding how exposure to media violence influences domestic violence perceptions, in comparison to the influence of media aggression on domestic violence perceptions, will allow for an overall perspective of how violent media in general influences domestic violence perpetration. Accordingly, the present study seeks to provide an empirical assessment of the relationship between violent media exposure and the perpetration of intimate partner abuse.

Although society believes that exposure to media violence Footnote 1 causes an individual to become violent, research has cast doubt on this belief, stating that violent media does not directly influence violent behavior at a highly correlated statistically significant level [2, 4, 21, 22, 65, 85]. In relation to media aggression Footnote 2 and domestic violence perceptions however, research has demonstrated a relationship between the two variables [11, 12, 23, 35, 39, 41, 47], such that an increased level of exposure to media aggression, for example, video games and movies depicting aggression towards women, influences individuals to become more accepting of aggression toward women.

According to The United States Department of Justice [75], domestic violence is defined as “a pattern of abusive behavior in any relationship that is used by one partner to gain or maintain power and control over another intimate partner” (para. 1). Emotional/psychological, verbal, physical, sexual, and financial abuse [42, 84], as well as digital abuse, are the different types of abuse that can occur amongst intimate partners.

In the United States alone, domestic violence hotlines received approximately 20,000 calls per day [51], with at least five million incidents occurring each year [34]. With the COVID-19 pandemic, the likelihood for domestic violence incidents to occur increased, while a victim’s ability to call and report decreased [18], due to individuals being locked down at home, being laid-off, or working from home. In examining the 1 in 4 women and 1 in 7 men who experience domestic violence at the hands of an intimate partner, 1 in 3 and 1 in 4, respectively, have experienced physical abuse [3], with 1 in 7 women and 1 in 25 men obtaining injuries from the abuse [51]. In addition, 1 in 10 women have been raped by an intimate partner, while the data on the true extent of male rape victimization is relatively unknown [51]. Even though domestic violence crimes make up approximately 15% of all reported violent crimes [77], almost half go unreported [57], due to various reasons (i.e., concerns about privacy, desire to protect the offender, fear of reprisal [19], relationship to the perpetrator [20]).

There are several risk factors that increase an individual’s likelihood of perpetrating domestic violence. Individuals who witnessed domestic violence between their parents [1, 17, 44, 49, 61, 73], or were abused as children themselves [32, 44, 68, 71, 79, 81], are more likely to perpetrate domestic violence than individuals who did not witness or experience such abuse. Research has found men who witnessed abuse between their parents had higher risk ratios for committing intimate partner violence themselves [61] and were more likely to engage in such violence [49], than men who did not witness such violence as children. Research has also shown that male adolescents who witnessed mother-to-father violence were more likely to engage in dating violence themselves [73]. Similarly, scholars have found women who witnessed intimate partner violence between their parents were over 1.5 times more likely to engage in such violence themselves [49], and adolescent girls were more likely to engage in dating violence when they witnessed violence between their parents [73]. Child abuse victims were more likely to perpetrate intimate partner violence as they aged, with 23-year-olds demonstrating a significant relationship compared to 21-year-olds [44], and males who identified as child abuse victims were found to be four times more likely to engage in such violence than males who had no history of such abuse [49]. Overall, both males and females who experienced child-family violence Footnote 3 were more likely to engage in both reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence [49].

Research has also found that being diagnosed with conduct disorder as a child or antisocial personality disorder as an adult, also increases the likelihood of domestic violence perpetration [7, 8, 17, 31, 45, 81], with antisocial personality disorder being a mediating factor between child abuse and later intimate partner violence perpetration [81]. Additionally, individuals who demonstrate antisocial characteristics during adolescence are at an elevated risk of engaging in domestic violence as adults [45]. Another key factor that influences domestic violence perpetration is having hostile attitudes and beliefs [5, 37, 48, 49, 70], with such attitudes being more of a predictive factor of intimate partner abuse than conduct problems [8]. Both men and women who approve of intimate partner violence are more likely to engage in or reciprocate such violence compared to those without such perceptions [49].

It has been long speculated that media violence is directly related to violent behavior and perpetration of violent crime, such as intimate partner abuse [6, 1433, 50]. However, research has found very weak evidence demonstrating a correlation between exposure to media violence and crime, with Pearson’s r correlations of less than 0.4 being indicated in most studies in this area [2, 21, 22, 64, 65, 85]. In fact, Savage [64] determined that exposure to violent activities through the media does not have a statistically significant relationship with crime perpetration. Likewise, Ferguson and colleagues’ [21, 22] work supported these findings, indicating that “exposure to television [violence] and video game violence were not significant predictors of violent crime” [21] (p. 396).

More recently, Savage and Yancey [65] conducted a meta-analysis of thirty two studies that tested the relationship between media violence (i.e., television or film) and criminal aggression. Lester (1989), Krittschnitt, Heath, and Ward (1986), Lagerspetz and Viemerö (1986), Phillips (1983), Berkowitz and Macaulay (1971), and Steuer, Applefield, and Smith (1971) were among the evaluated studies. Collectively, Savage and Yancey [65] concluded that the results from their analysis suggested that a relationship between violent media exposure and criminal aggression had not been established in the existing scholarly literature. Although there was evidence of a slight, positive effect of media violence on criminal aggression found for males. However, the authors noted several limitations among each of the evaluated studies that questions the generalizability of findings. As such, there is need for more work to be done in this area before firm conclusions can be drawn about the relationship between violent media exposure and violent behaviors.

Although research has demonstrated a lack of or weak correlation between media violence and violent behavior, research has found a moderate positive correlation between exposure to media aggression and domestic violence perceptions. Such research has found significant relationships between exposure to media aggression and a variety of delinquent perceptions, ranging from views on rape [47, 67] to domestic violence [11, 12, 39]. These views support and accept the rape of women and abusive tendencies towards an intimate partner.

For instance, Malamuth and Check [47] examined how exposure to movies that contained high levels of violence and sexual content, especially misogynistic content, influenced one’s perceptions. Individuals who watched such content were more likely to have rape-supportive attitudes than individuals who were not exposed to such movies. Simpson Beck and colleagues [67] found that rape supportive attitudes were more common among individuals who played video games that sexually objectified and degraded women. Such individuals were more likely to accept the belief that rape is an acceptable behavior and that it is the woman’s fault if she is raped, compared to individuals who did not play such video games.

Related, Cundiff [12] classified the songs on the Billboard’s Hot 100 chart between 2000 and 2010 into categories such as rape/sexual assault, demeaning language, physical violence, and sexual conquest, and found that throughout these songs, the objectification and control of women were common themes. In surveying individuals in relation to their exposure to such music, a positive correlation was found between an individual’s exposure to suggestive music, and their misogynous thinking [12]. Further, Fischer and Greitemeyer [23] found that individuals who listened to more aggressive music were more likely to have negative views of and act more aggressively towards women. Likewise, Kerig [39] and Coyne and colleagues [11] found that individuals who are exposed to higher levels of media aggression are more likely to perpetrate domestic violence offenses. This suggests that an increased exposure to media aggression influences an individual’s perceptions of domestic violence, and could, subsequently influence the perpetration of domestic violence.

A theoretical explanation for a relationship between violent media exposure and the perpetration of violent crime can be found in Cultivation Theory. Cultivation Theory assumes that “when people are exposed to media content or other socialization agents, they gradually come to cultivate or adopt beliefs about the world that coincide with the images they have been viewing or messages they have been hearing” [28] (p. 22). Essentially, this cultivation manifests into individuals mistaking their “world reality” with the “media reality,” thus increasing the likelihood of violence [26] (p. 350). Individuals who are exposed to violent media, are more likely to perceive their reality as filled with the same level of violence, resulting in an increased likelihood of the individual acting violently themselves. By identifying one’s reality with the “media reality,” individuals create their own social constructs and begin to believe that the violence demonstrated in the media is acceptable in life as well.

This cultivation and social construction creation based off of media is demonstrated through Kahlor and Eastin’s [38] examination of the influence of television shows on rape myth acceptance. Individuals who watched soap operas demonstrated race myth acceptance and an “overestimation of false rape accusations”, while individuals who watched crime shows were less likely to demonstrate rape myth acceptance [38] (p. 215). This demonstrates how the type of television show an individual watches, can influence how and what individuals learn from such viewing.

In relation to domestic violence perception, individuals who are exposed to violence in intimate relationships, or sexual aggression, whether through the media or in real life, are more likely to support or accept such actions over time [12, 28]. A longitudinal study conducted by Williams [82], examined cultivation effects on individuals who play video games. It was found that individuals who played video games at higher rates began to fear dangers which they experienced through the video games, demonstrating how individuals adopt beliefs based on their media exposure. Therefore, according to Cultivation Theory, individuals who are exposed to higher levels of violent media, are likely to learn from the media, and act based on this learning [12, 28, 82]. In relation to domestic violence, this work suggests that it is reasonable then to hypothesize that individuals who are exposed to higher levels of media violence are more likely to become supportive or accepting of domestic violence actions.

While prior research has explored the relationship between exposure to media aggression and domestic violence perceptions [11], [12, 23, 39, 47, 67], to date, we are unaware of research that has focused specifically on exploring the relationship between one’s level of exposure to media violence and domestic violence perceptions. As a result, the relationship between violent media exposure and domestic violence has yet to be fully examined. Further, research focusing specifically on media aggression, media violence, and violence perpetration has predominately focused on specific types of media (i.e., video games, movies, songs), often with the media platform and materials provided to the study participants by researchers. To date little research has investigated multiple forms of self-exposure to violent media and criminal perpetration. Moreover, previous research has failed to examine the effects of pleasure gained from such exposure, as we speculate that individual’s will be less likely to engage in consumption of media they find unpleasurable. Subsequently, the effects of media exposure are largely dependent on one’s disposition toward the content – which, admittedly, over time can be shaped by the content itself. Thus, we suggest that prior tests focusing exclusively on simulated exposure without consideration of pleasure have been incomplete.

Moreover, while there are scales that measure domestic violence perceptions (e.g., The Perceptions of and Attitudes Toward Domestic Violence Questionnaire – Revised (PADV-R), The Definitions of Domestic Violence Scale, The Attitudes toward the Use of Interpersonal Violence – Revised Scale, and various others compiled by Flood [25]), they are very specific in nature, making it difficult to use such scales outside of the specified nature for which they were created. In fact, these scales fail to examine the actual perceptions an individual has towards domestic violence, and when they do, they tend to examine domestic violence perpetrated by men, and not women. Thus, the current study sought to help fill some of these gaps in the literature.

There were three overarching goals driving the current project:

The data used in this study came from a sample of incarcerated offenders in two jails in New York and a prison in West Virginia. A sample of 148 convicted offenders Footnote 4 were surveyed between April 2018 and September 2018. The sampling procedure was one of convenience, in a face-to-face manner. A student intern at the prison asked inmates with whom she came into contact if they would be willing to take the survey. Such surveys were administered individually. For one of the jails, all inmates participating in educational classes were asked by the researcher to take the survey. Such surveys were administered in a group setting. A sign-up sheet was also placed in each pod for inmates to sign-up for survey participation. Each individual on the list was brought to a room occupied by only the researcher, with surveys being administered individually. For the second jail, correctional officers made an announcement in one of the pods, asking those who were interested in participation to let them know. Such inmates were individually brought to a room occupied by the researcher with a plexiglass wall between them. The surveys were administered via paper hard copy, with a researcher present to answer any questions the participants had throughout the survey process. Due to working with a vulnerable population, confidentiality was key. Confidentiality was maintained by not allowing any correctional staff in the room when the surveys were taken, and informed consent documents were kept separate from the surveys. Respondents were informed that their decision to participate in the study was completely voluntary, and that information would not be shared with law enforcement or anyone within the jail.

Two measures were used to assess domestic violence perpetration. First, participants were asked if they had been convicted of a domestic violence offense. While this is a good indication of domestic violence perpetration, it is not the “best” measure, as many persons who commit domestic violence are never convicted of the crime. As such, we employed a second measure of domestic violence perpetration. Specifically, participants were also asked if they had ever abused an intimate partner. Response categories were a dichotomous “yes” (1) or “no” (0).

We were interested in assessing the relationship between the intrinsic endorsement of domestic violence beliefs and domestic violence perpetration. Unfortunately, at the time of the study, the research team was not aware of any psychometrically sound measure of intrinsic endorsement of domestic violence beliefs available in the scholarly literature. Thus, we sought to create one. Specifically, we used an eighteen-item self-report scale to capture respondents’ intrinsic support of domestic violence. Some items included, “A wife sometimes deserves to be hit by her husband,” “A husband who makes his wife jealous on purpose deserves to be hit,” and “A wife angry enough to hit her husband must really love him.” Respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with the eighteen items on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”). Responses were summed to create a scale measure of intrinsic support of domestic violence beliefs with higher scores indicative of greater support of domestic violence. As indicated in Table 1, these items loaded onto one latent factor in an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.974).

Table 1 Results from exploratory factor analysis (EFA) for endorsement of domestic violence beliefsPrior research assessing the relationship between violent media exposure and crime has found mixed results [2, 11, 12, 21,22,23, 39, 47, 64, 65, 67, 85]. However, most of this work has employed only one measure of media exposure and has ignored the pleasure that one may receive from violent media – that is, whether they get enjoyment from the content. In an attempt to fill these gaps in the literature we considered three types of violent media exposure: (1) video games, (2) movies, and (3) television. Consistent with recommendations made by Savage and Yancey [65] our measures include an estimate of both media exposure (e.g., time) and rating of violence. Specifically, participants were asked to report the number of hours that they spent playing videogames, watching movies, and watching television each week. Next, they were asked to indicate the percentage of violence (0–100%) in the games, movies, and television they played and watched. Additionally, participants were asked to report how pleasurable they found the video games, movies, and television that they played and watched (coded, 0 = “Not Pleasurable” through 10 = “Very Pleasurable”). Responses to each of the three questions in the different blocks of media were multiplied together to create a scale measure assessing pleasurable violent media exposure with higher numbers indicative of greater pleasurable violent media exposure.

Four measures were used as control variables in this study: (1) age, (2) sex, (3) race, and (4) domestic violence victimization, as research has not examined if such victimization is related to victims’ perpetration of intimate partner violence. Specifically, participants were asked if they had ever been abused by an intimate partner. Responses were also dichotomous with 1 = “yes” and 0 = “no.” Age was a continuous variable ranging from 18 years old to 95 years old. Sex and race were dichotomous variables (i.e., 1 = “male” or “white” and 0 = “female” or “other”). Specifically, participants were asked if they had ever been abused by an intimate partner. Responses were also dichotomous with 1 = “yes” and 0 = “no.”

Table 2 displays the demographic information for the sample, as well as the descriptive statistics for key variables of interest. As indicated in Table 2, overall, the sample had an average age of 35.81 years. Most participants were male (91%) and identified as white (77%). About 45 percent of the sample reported being a victim of domestic violence. Regarding violent media exposure, participants indicated greater exposure to pleasurable violence in movies (M = 36.40, sd = 41.87) than to pleasurable violence in television (M = 29.73, sd = 38.73) and video games (M = 22.58, sd = 38.66). In the aggregate, participants did not show much intrinsic support for domestic violence (M = 34.02, sd = 18.22). However, 16.2 percent of the sample had been convicted of a domestic violence offense and 34.5 percent had admitted to abusing an intimate partner.

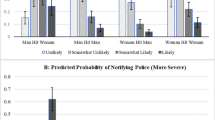

Table 2 Descriptive statistics (N = 148)Table 4 shows the results from logistic regression models estimating domestic violence convictions and self-reported domestic violence perpetration. The first model in Table 4 assessed the correlates of having a domestic violence conviction. Overall, the model fit the data well and explained about 14 percent of the variance in domestic violence in having a domestic violence conviction (Nagelkerke’s R 2 = 0.142). However, there was only one statistically significant predictor in that model, endorsement of domestic violence beliefs (b = 0.033, p < 0.05). Results show that a one-unit increase in intrinsic support for domestic violence was associated with a 1.033 increase in the odds of being convicted of a domestic violence offense.

Table 4 Logistic regression analyses predicting domestic violenceThe second model in Table 4 depicts the results from the logistic regression model estimating self-reported domestic violence perpetration. Overall, the model fit the data well and explained nearly 55 percent of the variance in abusing an intimate partner (Nagelkerke’s R 2 = 0.548). Interestingly, endorsement of domestic violence beliefs was not a significant predictor in this model (b = 0.004, p > 0.05). In fact, the only statistically significant predictor in that model was our measure of domestic violence victimization (b = − 3.533, p < 0.001). Results suggest that victims of domestic violence were 34.48 times less likely to report abusing an intimate partner than were non-victims, controlling for all other relevant factors. It is important to note that none of the measures of exposure to pleasurable media violence were related to either of our measures of domestic violence perpetration [74, 83].

Much of the prior work assessing the relationship between exposure to violent media and crime perpetration has ignored the pleasure component of media exposure and failed to assess multiple forms of violent media simultaneously while controlling for the endorsement of criminogenic beliefs and other relevant factors (e.g., prior victimization). The current exploratory project sought to help fill these gaps in the literature. Specifically, the current project had three main goals: (1) to establish a psychometrically sound measure of intrinsic support for domestic violence, (2) to assess the relationship between intrinsic support for domestic violence and domestic violence perpetration, and (3) to analyze the relationship between pleasurable violent media exposure and two different measures of domestic violence perpetration (i.e., conviction and “self-report”) while controlling for appropriate covariates (e.g., prior victimization, endorsement of domestic violence, etc.). Our research, using data from a sample of convicted offenders (N = 148), yielded several key findings worth further consideration.

First, results from Exploratory Factor Analysis showed that we were able to effectively create a psychometrically sound measure of intrinsic support for domestic violence. We encourage other researchers to adopt this 18-item measure of intrinsic support for domestic violence to use in future projects as both a predictor and an outcome measure. Future research should also explore how these beliefs come to be. Perhaps more importantly, though, through our data analyses we were able to establish a relationship between intrinsic support for domestic violence and being convicted of a domestic violence offense. That is, our results show that offenders who hold beliefs that favor the emotional and physical abuse of an intimate partner are more likely to have been convicted of a domestic violence offense than those who do not hold such views. This finding suggests that in order to help prevent domestic violence, researchers and practitioners need to develop strategies to avert, disrupt, or reverse the internalization of such beliefs. We suggest that targeting adolescents who are at risk of experiencing child abuse or witnessing abuse between their parents, may help prevent such individuals from internalizing the acceptance of such beliefs and reduce the chances that they will grow up to perpetrate domestic violence, as prior research indicates that they are a high-risk group Footnote 5 [36, 52]. For partners who have already engaged in violence toward one another, cognitive behavioral therapy programs, such as Behavioral Couples Therapy [53, 54, 62], are effective at changing domestic violence perceptions and reducing future violence [29, 63].

Third, our work highlights the importance of the role prior victimization plays in criminal perpetration. Interestingly, at the bivariate level, domestic violence victimization at the hands of an intimate partner was unrelated to a domestic violence conviction, but significantly and positively related to admitting to abusing an intimate partner. In fact, the relationship between being a victim of domestic violence and admitting to abusing an intimate partner was very strong (r = 0.637) [9]. This finding suggests that individuals who have been previously victimized at the hands of an intimate partner, are at an increased likelihood of abusing an intimate partner themselves. However, in multivariable modeling, this relationship switched directions, and prior victimization was found to be negatively related to self-reported domestic violence perpetration. In fact, with the addition of appropriate statistical controls in multivariable modeling, our findings suggest that those who had been abused by an intimate partner were more than 34 times less likely to report abusing an intimate partner. This is an interesting and difficult finding to interpret because it opposes prior work indicating that victimization experiences, especially among the young [32, 44, 71, 81], and witnessing domestic violence [1, 17, 44, 49, 61, 68, 73, 79], can be positively related to perpetration. Initially, we speculated that the reason for this observed relationship had to do with controlling for the endorsement of domestic violence beliefs. However, the significant negative relationship between victimization and domestic violence perpetration existed in auxiliary analyses that removed the variable assessing endorsement of domestic violence beliefs from statistical modeling. Thus, we offer two plausible explanation for the observed relationship. First, this finding may reflect some form of empathy that serves as a protective factor against domestic violence perpetration – controlling for other relevant factors, such as demographics, endorsements of domestic violence beliefs, and pleasurable violent media exposure. That is, victims of domestic violence understand the horrific pain caused by intimate partner abuse, and in an attempt to avoid instilling such pain onto their spouse, they refrain from acting out aggressively against them. Second, this finding may simply be the result of sampling error. There was no relationship found between domestic violence conviction and domestic violence victimization in statistical modeling. As such, the relationship found between domestic violence victimization and self-reported domestic violence perpetration could merely be due to the fact that the measure was self-reported. That is, it may be that victims of domestic violence are less willing to admit to domestic violence perpetration than non-victims, for whatever reason. Future research should explore these findings more in relation to these two hypotheses.

There are several limitations to our study that warrant disclosure. First, results reported above come from a small convenience sample of offenders incarcerated in New York and West Virginia. Thus, the findings from this exploratory study are not generalizable beyond these parameters. Second, the data had temporal ordering constraints. The dependent and independent variables were collected at the same time. Accordingly, our use of the term “predictor” in multivariable modeling is more consistent with “correlation.” Due to temporal ordering issues, it is unknown if individuals prone to violence seek out violent media, or if violent media causes such individuals to become violent. Future research should employ probabilistic sampling techniques, collect data from more urban sites, and use longitudinal research designs. Third, our measures of violent media exposure were not ideal. Notably, while more robust than prior estimates of violent media exposure, our measures of violent media exposure looked at general media violence across three different types of media—television, movies, and video games. It would be better for future researchers to examine the impact of specific types of violence depicted in media, such as domestic violence, on specific types of violent crimes.

Future work should also take steps to better explore this relationship from a theoretical lens, such as Cultivation Theory, “mean world” hypothesis, and catharsis effects. Future work may also benefit from approaching this topic inductively, by asking respondents to list the media they consume and then exploring the relationship between this media consumption and various forms of crime. For instance, it may be prudent to explore the relationship between exposure to types of pornography and acceptance of domestic violence beliefs, and subsequently, perpetration rates. This could further provide evidence of a media cultivation or catharsis effect. Lastly, the survey questions used wording pertaining to “husband” and “wife,” thereby limiting the range of domestic violence. Future research should change the wording in the survey, to examine perceptions of domestic violence between intimate partners, and not just between spouses.

The relationship between exposure to violent media and crime perpetration is complex. Results from the current study suggest that exposure to various forms of pleasurable violent media is unrelated to domestic violence perpetration. When considering domestic violence perpetration, prior victimization experience and endorsement of domestic violence beliefs appear to be significant correlates worthy of future exploration and policy development.

Media violence is defined as various forms of media (i.e., television, music, video games, movies, Internet), that contain or portray acts of violence [10].

Media aggression, for the purpose of this study, is defined as various forms of media that contain or portray acts of aggression. Aggression is defined as: “[1)] a forceful action or procedure (such as an unprovoked attack), especially when intended to dominate or master; [2)] the practice of making attacks or encroachments; [and 3)] hostile, injurious, or destructive behavior or outlook, especially when caused by frustration” [13].

A combined measure of childhood physical abuse victimization and witnessing violence between parents [49].

Four respondents did not provide their biological sex.Programs affective at reducing the likelihood of violence include, but are not limited to [50], Safe Dates [27], The Fourth R: Strategies for Healthy Teen Relationships [81], Expect Respect Support Groups [58], Nurse Family Partnership [15, 55, 56], Child Parent Centers [59, 60], Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care [16, 24, 30], Shifting Boundaries [72], and Multisystemic Therapy [66, 80].

This project received no funding for any element of the project, including study design, data collection, data analysis, or manuscript preparation.